Making a Federal Case Out of Cooperstown

June 26, 2022 by Frank Jackson · 1 Comment

The Federal League expired more than a century ago and lasted but two seasons (1914 and 1915), so its legacy is minimal. The eight franchises are little noted nor long remembered, though savvy fans may be aware that Wrigley Field , originally known as Weeghman Park (named after team owner Charles Weeghman), was built for the Chicago FL franchise.

But what about the players? Despite the short duration of the league, six of the players who donned FL uniforms ended up in the Hall of Fame. Obviously, the two FL seasons played a negligible part, if any, in the Hall of Fame voting, but it’s worth a look to see how those six players performed during their one or two years as Federales.

After the 1913 season, Federal League agents began contacting major league players. Given the low salaries of the dead ball era, most players were willing to at least entertain an offer. Not surprisingly, all the HOF honorees who crossed over to the FL were veterans.

Obviously, adding a familiar name to the roster added some marquee value to a new team in a new league. A number of MLB players ( e.g ., Cy Falkenberg, Benny Kauff, George Stovall, Ed Ruelbach, Howie Camnitz, Claude Hendrix, Hal Chase) chose to migrate to the FL. The biggest name, however, was the one that got away: Walter Johnson .

At age 25, Johnson was in his prime. He had won 25 games in both 1910 and 1911, and followed that up with a 33-12 record in 1912. Then came the real show-stopper, a 36-7 record in 1913. His ERA was below 2.00 during that four-season span, including a jaw-dropping 1.14 in 1913. Add to all this his reputation for clean living and sportsmanship, and he was a highly marketable athlete.

Hard to believe, but after Johnson’s 33-12 record in 1912, the Senators did not give him a raise for 1913. As a newly married man, Johnson was doubtless looking to the future, so he was ready to lend an ear to the Federal League’s offer.

Reportedly, Johnson had agreed to a $70,000 contract ($20,000/year for three years plus a $10,000 bonus) with the Chicago FL franchise. Apparently, he had a heart-to-heart with Senators manager Clark Griffith (in 1914 he owned only a minority interest in the team) and decided to remain with the team despite its reputation as a shoestring operation. So Johnson re-upped with the Senators for $12,500/year for three years.

The fate of Johnson’s $10,000 bonus was a curious one. Obviously, he had to return it, but White Sox owner Charles Comiskey reimbursed Johnson. This might seem to be an obvious conflict of interest, but given Johnson’s power as a drawing card, it made sense for Comiskey to cough up money to keep him in the AL, even if it might negatively affect the White Sox won-loss record.

Also, Comiskey might have been attempting to minimize the effect a third Chicago franchise would have on his bottom line (as it turned out the Cubs suffered at the box office in 1914 and 1915 but White Sox attendance held steady). Hard to believe that AL President Ban Johnson would let this transaction slide (there was no MLB Commissioner at that time), but he and Comiskey were old buddies. Perhaps he felt that Comiskey’s gift was in the best interests of the American League–which it was.

One can understand Griffith’s panic at the thought of losing Johnson. When Johnson came aboard in 1907, the Senators were a last-place team. They bounced back and forth between next-to-last and last for the next few years, but during Johnson’s 30+ win seasons of 1912 and 1913, they rose to second place. Clearly, Johnson was essential for the Senators to compete. He couldn’t take the mound every day, however, and as it turned out, the Senators didn’t win a pennant till 1924 when Johnson was 36 years old.

Even stars who rebuffed the Federal League benefited from the situation. Ty Cobb, for example, got a nice raise from $11,333 to $15,000 for the 1914 season and $20,000 the following year. Deservedly, he was the highest-paid player in the game. He used the FL offer of five years for $75,000 as leverage.

An even bigger FL contract was offered to Tris Speaker: $100,000 for three years, managing and playing for the Brooklyn Tip-Tops. The Red Sox countered by almost doubling his salary, from $9,000 to $17,500, and that was without managerial duties (which he eventually assumed as a member of the Cleveland Indians in 1919).

Obviously, that kind of star power would have made FL teams more attractive and would have negatively impacted ticket sales in overlapping MLB (and minor league) markets. Had the Feds lasted more than two years, MLB history would be entirely different. But “what if” has unleashed more speculation than any other phrase in history, so let’s leave that rabbit hole unexplored.

Though Johnson, Cobb, Speaker, and other future HOF members did not cross over to the dark side, a few did so. For the most part, they were veterans whose best days were behind them. They were:

JOE TINKER (HOF 1946)

The first name in the legendary Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance triumvirate, shortstop Joe Tinker spent 11 years (1902-1912) with the Cubs during their glory years. He was traded to the Reds after the 1912 season and he responded with a career-best .317 BA while serving as a player-manager. If he felt any sorrow about leaving Chicago, it was likely muted by the hefty salary increase (from $5,600 to $10,000) the Reds gave him.

Nevertheless, when the Chi-Feds offered him the same gig with a $2,000 raise, he jumped at it, particularly since the Reds were attempting to trade him to Brooklyn. In fact, Tinker was the first player to sign a contract with the FL, giving instant credibility to the new league.

Tinker’s stay with the Chicago Feds (known as the Whales in 1915 after a name-that-team contest) was a productive one. Reported attendance figures were suspect, but there was no doubt the Feds had eaten into the Cubs’ fan base. The Cubs fell from 419,000 in 1913 to 202,516 in 1914. Their profits plunged from $100,000 to $20,000.

Tinker managed the Chicago franchise to a second-place finish (87-67) in 1914 and a pennant (86-66) in 1915. After the FL folded, team owner Charles Weeghman purchased the Cubs before the 1916 season and retained 11 players from the Whales roster, including Tinker as manager. Tinker’s playing days, however, were all but over, as he sent himself to the plate only 12 times in 1916.

After his playing days, Tinker retired to Orlando, where he was involved in a number of real estate ventures. Orlando’s Tinker Field, a longtime spring training site (1923-1990) was named in his honor. I guess he was dishonored when the park was razed in 2015.

EDDIE PLANK (HOF 1946)

Joining Tinker in the HOF Class of ’46 was Eddie Plank. Though he did not become a big leaguer till age 25, Plank was a mainstay of the Philadelphia A’s pitching staff from the start, namely the 1901 inaugural AL season.

Starting with his 17-13 rookie season, Plank never won less than 14 games per year through 1914, and won at least 20 games seven times. By the end of the 1914 season, he had won 294 games. But owner/manager Connie Mack felt he could not compete with the FL, so he decided to blow up his team and start over. Eddie Plank, age 39, was released. Latching on with another MLB team for a decent salary was unlikely.

Then the FL St. Louis Terriers came calling. Plank signed up and responded with a 21-11 record and a 2.08 ERA. Of all the members of the 300-win club, Plank is the only one to reach that plateau while with the Federal League (he did so on September 11 in a 12-5 victory over the Newark Peppers).

The league went bye bye after that season, but Plank had convinced the St. Louis Browns that he wasn’t washed up. Despite his age, they signed him to a contract for 1916 and he responded with a 16-15 record and a 2.33 record. 1917 was his final season, a mere 5-6, albeit with a 1.79 ERA in 131 innings.

Had he not proved his mettle in the FL, his MLB career might have ended after Connie Mack let him go.

Purists who sniff that the FL wasn’t really a major league operation should note that even if you subtract the 21 games Plank won for the Terriers, he also won 305 games in the AL. So there’s no need to attach an asterisk to his accomplishment. No matter how you slice it, Plank was the first left-hander to reach the 300 win mark. (Warren Spahn, the all-time southpaw leader in wins with 363, surpassed Plank’s total of 326 in 1962; Steve Carlton did so in 1987 and finished with 329.)

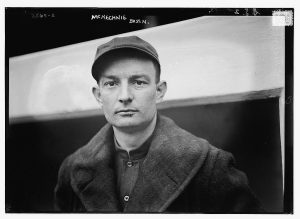

MORDECAI “THREE FINGER” BROWN (HOF 1949)

Like Joe Tinker, “Three Finger” Brown was a key member of the great Chicago Cubs teams during the first decade of the 20 th Century. He won 20+ games from 1906 through 1911, but in 1912, he was 5-6 in just 88.2 innings, so the Cubs released him.

Despite a steep pay cut (from $7,000 to $5,000), he resurfaced with the Reds in 1913 at age 36. The results were mixed: 11-12 with a 2.91 ERA in 173.1 innings. If he could continue his career in the National League, he was not likely to receive a raise, but the St. Louis Terriers were willing to double his salary for the 1914 season if he would serve as player-manager.

One suspects Brown didn’t take much time pondering that offer. He had followed Joe Tinker to Cincinnati in 1913, and he went with him again to the Federal League in 1914. Indeed, he signed up the same day Tinker did.

Brown played with both the St. Louis Terriers and the Brooklyn Tip-Tops in 1914 and went 14-11 with a 3.52 ERA. He was reunited with Tinker in 1915 when he went 17-8 with a 2.09 ERA for the Chicago Whales. Brown did not appear to be washed up, so when Tinker took over the Cubs in 1916, he took Brown along. After an indifferent season with the Reds, he finished his career with minor league stops in Columbus (OH), Indianapolis, and Terre Haute, and finally retired at age 43.

CHIEF BENDER (HOF 1953)

In a sense, Chief Bender was a younger version of Eddie Plank. Bender didn’t join the A’s till 1903 but he was only 19 in his 17-14 rookie year. Joining Plank in the starting rotation, he won 193 games through 1914. He turned 30 during the 1914 season and responded with a 17-3 record and a 2.26 record. Nevertheless, Connie Mack, not wanting to get into a bidding contest with the FL, released Bender.

One would think Bender still had some mileage left on his career odometer, and the FL Baltimore Terrapins felt likewise. The Terps had a dismal season (47-107) in 1915, and Bender suffered the worst year of his career, going 4-16 with a 3.99 ERA.

Even so, the Phillies, figuring that Bender’s name recognition in Philadelphia might draw a few fans, took a flyer on him for 1916. The results were mediocre (7-7, 3.74) but in 1917 he went 8-2 with a 1.67 ERA. So he ended his MLB career on a high note (aside from a one-inning outing with the White Sox in 1925) before embarking on a lengthy career as a minor league manager and coach.

Notably, Bender continued to pitch in the minors, going an astounding 29-2 for Richmond in the Class C Virginia League in 1919, and 25-12 for New Haven in the Single-A Eastern League in 1920.

Bender’s FL sojourn is a curious anomaly in an otherwise outstanding resume. Perhaps there was something about Baltimore that disagreed with him. When he pitched for (and managed) the Baltimore Orioles of the Double-A International League in 1923, he registered a 5.03 ERA, the highest mark of his career, aside from that one-inning stint in 1925.

BILL McKECHNIE (HOF 1962)

Bill McKechnie was a five-year veteran when he made the jump to the FL in 1914. Beyond that, however, there wasn’t much to say about him. He was your basic utility infielder. Like many of his brethren, his time on the bench sharpened his baseball smarts if not his skills.

His jump to the Federal League resulted in the only .300 season of his MLB career–and he was playing full-time. He hit .304 (173 for 570) for the Indianapolis Hoosiers in 1914.

In 1915, the Indianapolis franchise moved to Newark where the team was known as the Peppers. (One wonders if the team physician was known as Dr Pepper.) Hence the team was the only MLB franchise to be based in New Jersey in modern baseball history (the Dodgers played some games in Jersey City in 1956 and 1957, but they were still based in Brooklyn).

In Newark, McKechnie’s batting average dropped off to .251, but it proved to be a pivotal year in his career. Though manager Billy Phillips had led the franchise to the FL championship the year before, he could only manage a so-so 26-27 record in Newark, so he was fired as manager and McKechnie became player-manager, leading the team to a 54-45 record the rest of the way.

This in itself is not particularly noteworthy, but it enabled him to get his managerial feet wet. Since his HOF induction was based on his career as a manager, it is worth noting that the Federal League was his first gig.

After the FL folded, McKechnie resumed his MLB playing career . He played from 1916 through 1920 (aside from the war year of 1919) and topped off his playing career at age 34 in the American Association with the Double-A Minneapolis Millers, for whom he hit .321 (212 for 661).

His managerial career in the NL spanned 1922 through 1946 (save for 1927). He won pennants with the Pirates (1925), Cardinals (1928) and Reds (1939 and 1940), and won the World Series with the Pirates and 1940 Reds.

Like Joe Tinker, he retired to Florida and had a spring training ballpark named after him. Unlike Tinker Field, Bradenton’s McKechnie Field is still around, and has been the spring training home of the Pittsburgh Pirates since 1969.

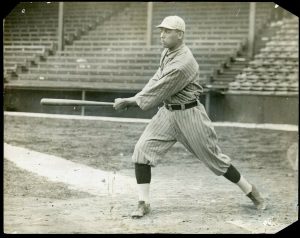

EDD ROUSH (HOF 1962)

While there was no shortage of FL players with MLB experience, few had their best years ahead of them. The most notable exception was Edd Roush.

Technically, Roush was a veteran but just barely. He came to bat 10 times for the White Sox in 1913. His first MLB hit (and his only hit that season) came off Chief Bender, who would join him in the Federal League in 1915. Playing for the Lincoln (NE) Railsplitters of the Single-A Western League at the end of the 1913 season, Roush was contacted by the FL, who offered to double his salary.

Playing for the Indianapolis Hoosiers in 1914, the 21-year-old Roush hit .325 in part-time duty (54 for 166). When the franchise shifted to Newark, he shifted to full-time status and responded with a .298 average (164 for 551). Given his youth, he obviously had a future in MLB, so John McGraw signed him up for the Giants.

Roush’s half-season stint with the Giants was not successful (13 for 69). He was not fond of McGraw and apparently the feeling was mutual, as McGraw traded him to Cincinnati (along with Bill McKechnie – and Christy Mathewson, who was to serve as the Reds manager). McGraw rued that trade for a decade.

Only 23, Roush finished out the 1916 season with the Reds and hit .287 playing full-time. He would remain a fixture in center field with the Reds through 1926. During that time he never hit less than .321. That figure in 1919, when the Reds beat the Black Sox in the World Series, won him his second batting title (the first came in 1917 with a .341 mark).

Despite his differences with McGraw, Roush was reunited with him in 1927 when the Giants purchased him for $7,500. He played three seasons with the Giants, sat out the 1930 season in a salary dispute, then returned for a curtain call with the Reds in 1931.

He retired after the ’31 season with 2,376 hits and a .323 lifetime average and, like McKechnie, made his home in Bradenton. In fact, when he died at age 94 on March 21, 1988, it was before a game at McKechnie Field. At the time, Roush was the oldest living member of the HOF and the last veteran of the Black Sox series.

JOHN MONTGOMERY WARD (HOF 1964)

Monte Ward did not play in the Federal League (he was 54 years old on opening day in 1914) but he did serve as Business manager of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops in 1914. This was the third Brooklyn franchise Ward had been associated with. Having founded the Players League in 1890, he served as player-manager for the Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders; after that league went bust, he spent the next two years managing and playing for the NL Brooklyn Bridegrooms.

So he came to Brooklyn with one outlaw league and left with another one. His employment with the Tip-Tops was the last job he ever held in baseball. Given his long and multi-faceted baseball career, it was hardly one of the highlights.

The FL veterans probably didn’t boast of their exploits in that league, but they have nothing to apologize for. Had their previous teams been willing to pay them more, they would have stayed put. Had the FL caught on, they might have been looked on as pioneers rather than traitors.

Doubtless many visitors to Cooperstown see “FL” on the plaques of the above honorees and wonder what it stands for. The footnote league, perhaps?

Well, if you are a dutiful reader of footnotes, you know that there are some pretty tasty tidbits of information contained therein.

A few more of those signings (Ty Cobb and Walter Johnson) and the Federal League would have succeeded. As it is, the two seasons produced largely competitive baseball. And it’s important to recall that the Federal League did not fail. Rather, a settlement was reached with Major League Baseball, whose owners were tired of paying higher salaries to keep players from jumping. Sure enough, without the competition, salaries went down.